Residents of King Manor

Since the home’s construction circa 1750, there have been several families and individuals who called King Manor home. Here you can learn a little about some of the people who would have lived and worked on the property between 1805 and 1896.

The King Family

The King Family lived on the 160+ acre property for ninety-one years over three generations, from Rufus King to his granddaughter, Cornelia King. Rufus and Mary raised most of their children here, and their grandchildren often spent time living at the Manor, helping their parents look after the place when Rufus’ political work took him to Washington, D.C.

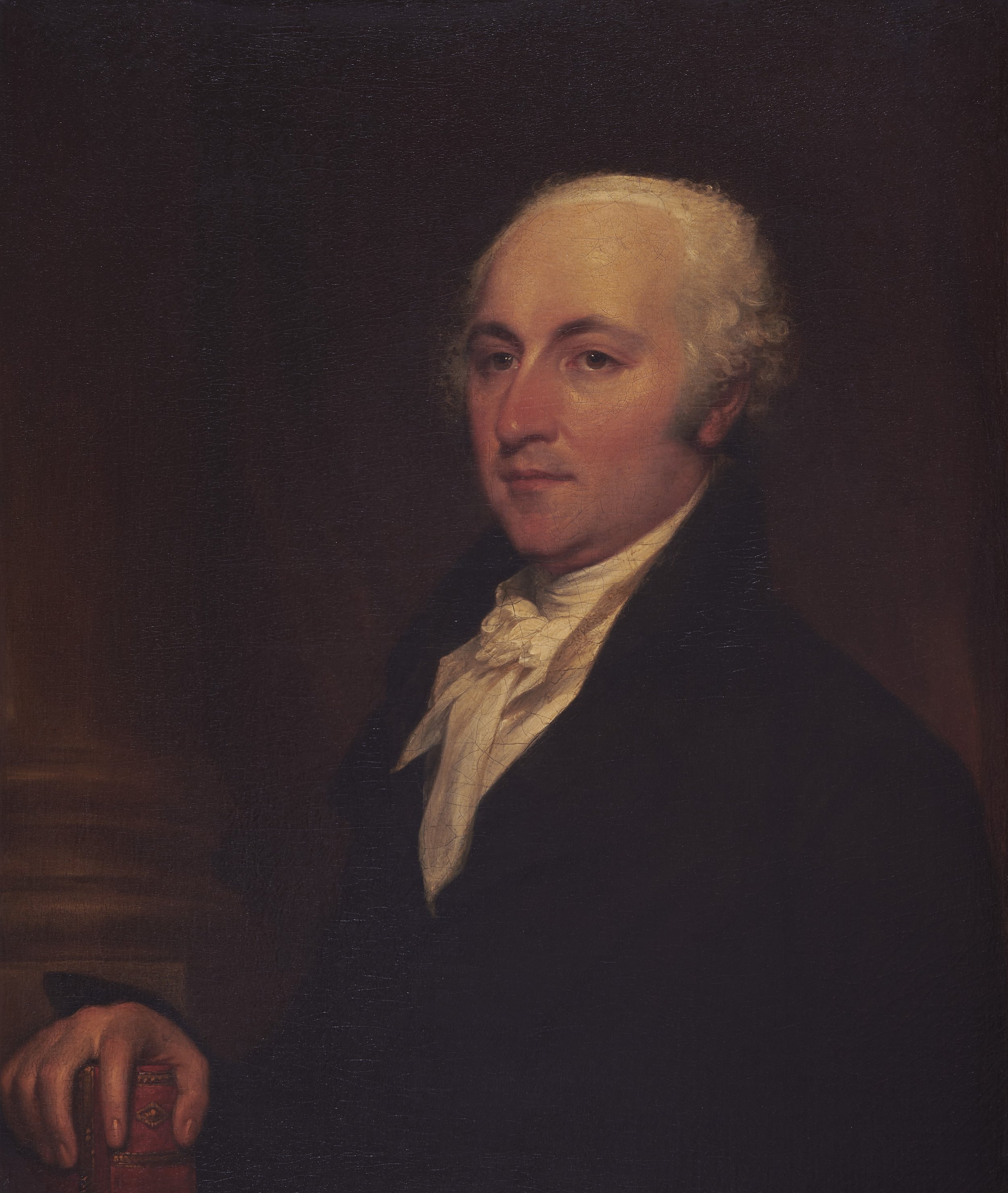

Rufus King

(1755 - 1827)

Rufus King was the eldest son of a prosperous Maine merchant. After graduating at the top of his class at Harvard in 1777 and briefly serving in the American Revolution in Rhode Island, King studied law in Massachusetts. He proved a good lawyer and was quickly elected into public service, beginning his career as a member of the Massachusetts state legislature and a representative in the first years of the United States federal government. In 1787 he helped to frame, sign, and ratify the U.S. Constitution. Shortly thereafter King moved to New York City and was elected to the Senate after one month of residency in the state. As a member of the Federalist Party, he aimed to implement a strong, central government.

In 1796 Rufus was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary (or, ambassador) to Great Britain where he helped shape American maritime policy in the earliest years of the new nation. He served in the post until 1803. King retired from public life to his country house in Jamaica, Long Island — King Manor — in 1806 but eventually returned to the Senate during the tumultuous years of the War of 1812. During the conflict Rufus stressed the importance of country over party and became a rallying point for unity in the nation. He was the last standard bearer for the Federalist Party and was defeated in the 1816 presidential election against James Monroe.

A lifelong anti-slavery advocate, King returned to the Senate yet again in his twilight years to speak out against the spread of slavery during the debates on the Missouri Compromise, 1819-1821. King’s outspoken anti-slavery position was radical for his time and earned him both respect and ire from his fellow Congressmen.

Rufus King lived off and on at King Manor until his death in 1827. He was buried next to his wife Mary at Grace Episcopal Church, a block east of King Manor on Jamaica Avenue.

Mary Alsop King

(1769 - 1819)

Mary Alsop King was born on October 17, 1769. She lost her mother, Mary Frogat Alsop, at the young age of three. She was therefore raised by her father, John Alsop, who was a prominent New York citizen and a prosperous merchant. Later, Mary’s father served as a delegate to the first two Continental Congresses, opening his home to board another of the delegates — a young Rufus King. On March 30, 1786, Mary Alsop was married to Rufus King.

Mary’s role at King Manor would have been one of great responsibility, managing a large household to the high standards expected of a senator’s wife in the early 19th century. She was well-educated and even musical, having played the fortepiano from a very young age. Though few of her own words survive, Mary was often regarded by others as a woman of dignity and compassion. We know she took a vested interest in the lives and well-being of the hired help at King Manor through her letters to her children, with whom she kept regular correspondence throughout her life. Mary lived at King Manor until her death in 1819. She was buried at Grace Episcopal Church, a block east of King Manor on Jamaica Avenue.

John Alsop King

(1788 - 1867)

The eldest child of Rufus King and Mary Alsop King, John purchased King Manor from his father’s estate in 1827 and continued to use the property as a working farm. John followed in his father’s footsteps into politics and was elected twice to the New York State Assembly and Senate, where he spoke out against the 1840 “gag rule” that existed to stop the receipt of abolitionist petitions to Congress. In 1849 John was elected to Congress where he established his reputation as an opponent of slavery. He also opposed connecting the admission of free states to the Union with that of slave states. John was Governor of New York from 1857-59, and fought for the arrest of “Blackbirders,” men who seized free black New Yorkers and sold them into slavery. John was instrumental in the formation of the Republican Party and cast his vote as an elector-at-large for Abraham Lincoln in 1860. During John’s ownership, King Manor was referred to as the “Governor’s House” and retained this name well into the 20th century. He is buried behind his parents at Grace Episcopal Church, a block east of King Manor on Jamaica Avenue.

Charles King

(1789 - 1867)

Charles was eighteen years old and studying in Europe when the Kings moved into their home in Jamaica. He became the editor of a newspaper named New York American, and eventually the President of Columbia College. He often looked after King Manor for his parents while Rufus and Mary were in Washington, DC on Senate business.

James Gore King

(1791 - 1853)

James was sixteen years old and attending a boarding school in France when the Kings moved into their home in Jamaica. After serving in the War of 1812, he grew up to become a financier and banker. One of his greatest accomplishments was helping secure a loan from Britain to help relieve the United States Panic of 1837. He also played an important role in completing the building of the New York and Erie Rail Road.

Edward King

(1795 - 1836)

Edward was seven years old when the Kings moved into their home in Jamaica. He was an active child, who his mother notes was eager to go sledding every winter. In adulthood, he became a lawyer and in 1815 moved to Ohio, where he became a state legislator and founded the Cincinnati Law School.

Frederick Gore King

(1802 - 1829)

Frederick, called “Fitty” by his family, was three years old when the Kings moved into their home in Jamaica. Mary called him a “chatterbox” and it is mentioned that he was rather articulate even as a very small boy. Later, Frederick became a successful doctor who was famous for his lectures on anatomy. He died of yellow fever after treating quarantined sailors during an outbreak in 1829.

The Workers

The people who worked at King Manor were a diverse group of folks, and held several positions at the Manor. Some lived there full time, some had homes in the village of Jamaica, and others were only hired temporarily as seasonal workers. Since King Manor under the King Family’s ownership was an anti-slavery household, all workers were paid a living wage. In the early 1800s, both Black and white workers were employed at King Manor in equal number. By the time John King took ownership of the Manor in 1827, however, Irish and Scottish immigrants made up the majority of the workforce.

We have no images of the people who worked at King Manor, only glimpses into their lives through letters sent by their employers and the census records. Years listed indicate their term of service at the Manor.

Hannah

Maid (c. 1810 - C. 1820’s)

Mentions of Hannah begin in letters between the King family members in 1816, though the tone in Mary Alsop King’s writing about Hannah might suggest she had been working for them even earlier. Indeed, the Kings seem to have had a special sort of employer/employee relationship with Hannah and that she was somewhat of a fixture; in 1817, Rufus’ best friend Christopher Gore mentions that he was “happy to learn that you (Rufus) were so well taken care of by Hannah.” We do know that Hannah was one of the servants kept on even while the Kings were away in Washington, DC. Hannah would also have used one of the small servants bedrooms as her own.

We know that sometime in early 1816, Hannah broke her arm. Mary King asked after her in two April 1816 letters, telling her to take it easy until she was well. Mary would also send her instructions from Washington, and she seems to have trusted Hannah’s skills and integrity in her job, since she always gave Hannah the power to determine when and how the tasks should be completed.

Thomas

Coachman (c. 1814-1815)

Thomas is a bit of an infamous fellow at King Manor. After being dismissed in 1815 by Rufus King, Thomas stole Rufus’ favorite Dalmatian dog when he left the property. Rufus sent a letter, pleading for Thomas to return his beloved pooch. Fortunately, the dog was brought back safely.

While he was employed here, Thomas apparently enjoyed doing figure eights with the coach out front of the house.

Hetty

Maid (1816 - 1817)

While away in Washington, DC, Mary Alsop King asked her son Frederick in 1816 to remind Hetty to “go to work with the soap,” meaning she needed to clean the house. At that time, Hetty may have only been with the family for a little over a month and a half, so it’s possible she was still learning her employer’s expectations.

Hetty occupied one of the bedrooms upstairs (in what is now the office area). She had her own room, provided by a wall that was added by the Kings to give their live-in staff private spaces. She was dismissed in 1817, a year after she was first mentioned in Rufus and Mary’s letters, and was paid $114.25 upon her dismissal.

Valentine

Gardener (1821 - c. 1830)

Valentine (his surname, first name unknown) began work at King Manor on November 27th, 1821. His brother, King Manor’s gardener before him, became unwell and recommended Valentine as a suitable replacement. Valentine was responsible for maintaining the manor’s kitchen garden. This was a sizable plot which grew herbs used in cooking, scents, and remedies, as well as flowers and vegetables not being grown as a crop in the fields. He also tended the trees in the Kings’ apple orchard and peach trees, a specialized task. Rufus wrote to John in 1824 to ask him to tell Valentine to plow and get ready for planting corn, and there are several accounts of him planting and tending an oat crop as well.

Valentine’s relationship with the King family seems to have been very amicable, to the point that John Alsop King supported Valentine in a dispute with the King family’s coachman in 1822. John even went so far as to suggest to his father that they fire the coachman for his behavior toward Valentine. Rufus took his suggestion -- he sent money not two days later to “settle with the Coachman.” (Doesn’t seem like Rufus had very good luck with coachmen!)

Peter, Dominic, and James

Farmhands (c. 1830’s)

We don’t know much about Peter, Dominic, and James. They were all Irish immigrants working at King Manor during the 1830 census, and we do know they were laborers, or farmhands. Their work was likely seasonal, and they may have been hired back several years in a row, but when it came time for Rufus and Mary to spend time in Washington, they would have been dismissed for the season.

Mary Gillroy

Cook (c. 1860’s)

Mary Gillroy was born in Ireland and was listed as John Alsop King’s cook on the 1860 census. She was 24 years old at that time. Mary would have had a difficult job. Her day would have begun in the wee hours of the morning, and she would have been working in the kitchen up to 13 hours a day, depending upon the size and scope of the meals. She may have had some assistance, but she would have been in charge of the operation. She would also have needed to understand “marketing and accounts,” which was a specification Rufus wished for in a cook in an 1809 letter.